Worries about Lakewood’s future had begun in mid-1951 when Long Beach city officials described an ambitious plan to annex Lakewood bit by bit. As John Todd, recalled in his 1969 memoir:

In July of 1951, the city of Long Beach released a 130-page document with exhibits and supporting data entitled “An Analysis of the Advisability of Annexing All or Part of the Lakewood Area to the City of Long Beach.” This plan was written by John Budd Wentz, Administrative Assistant to the city manager of the city of Long Beach.

The plan supposedly studied the feasibility of the Lakewood area remaining unincorporated, being incorporated, or annexing to the city of Long Beach, and concluded that economically, socially, and geographically the Lakewood area belonged to Long Beach and should be annexed to Long Beach.

Budd Wentz contained within his report maps and diagrams suggesting the step-by-step, piecemeal annexation of Lakewood. He advocated dividing the Lakewood area into small individual increments, trying to obtain a sympathetic majority in each increment and proceeding to elections almost on a daily or day-by-day basis. By this method, the opposition would be divided; it would be difficult to oppose day-by-day elections, and annexation to Long Beach was certain, he reasoned.

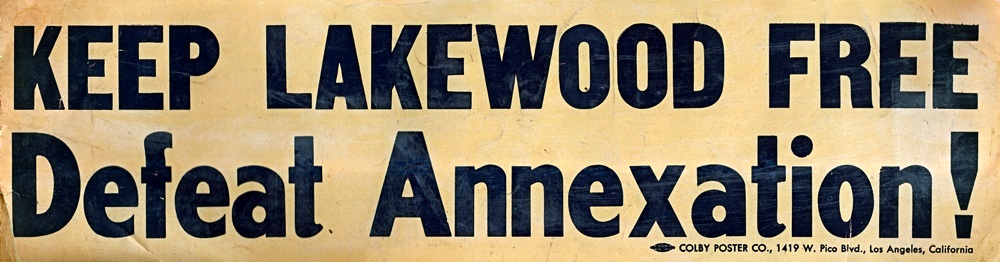

But they underestimated the people of Lakewood. They fought, and how they fought. Their success under such odds was overwhelming.

City officials in Long Beach had set the stage for the city's expansion long before 1951. The Lakewood area was already surrounded on the north, east, and west sides by 500-foot-wide, uninhabited “shoestring strips,” as well as by a wide “shotgun strip” along Carson Street that bisected the neighborhoods developed by the Lakewood Park Corporation on the south. (Video: Annexation threatens Lakewood)

The city of Long Beach had purchased the “shoestring strips” from the Montana Land Company decades before to prevent the southern expansion of Los Angeles and to put the land of the Montana Ranch within Long Beach’s eventual political control. The "shotgun strip" provided Long Beach access to the aquifers beneath Lakewood.

The Wentz Report in 1951 laid out an annexation plan that served Long Beach's political and economic future, including expansion of city-owned water and gas utilities, but Lakewood residents were undecided if annexation would be the answer for their future.

As the Long Beach Independent newspaper reported in February 1952, “A whopping majority of the residents questioned by Independent reporters during the past month said they were not ready for a change in local government – at least for some time to come. Thirty-six percent had no opinion at all on the subject. Of those who were ready ‘to speak for the record,’ 58% voted in favor of keeping their county-type government as it is.”

Only 16% favored incorporation. “What Lakewood wants more than anything, is to keep its civic identity and to have considerable authority in its local level of government,” concluded the Independent.

Annex or not? Lakewood residents were undecided in 1952.

Annex or not? Lakewood residents were undecided in 1952.

But annexation to Long Beach still seemed like a good idea to some when they were given the opportunity. They were in 1953. The Lakewood Plaza Citizens Improvement Association urged voters to choose annexation to Long Beach with an appeal to their pocketbook.

"Total savings by annexing to Long Beach would be $25.00 a year” compared to county taxes, the association’s pro-annexation flyer predicted. Long Beach also had its oil wealth (from the city’s tidelands oil fields) and the advantage of its excellent police and fire services. These arguments worked for the two Lakewood Plaza neighborhoods south of Heartwell Park. They voted to join Long Beach.

Worried that further annexation would strangle the rapid growth of Lakewood Center, Ben Weingart briefly explored the option of incorporating the shopping center and a few blocks of homes around it as a separate city.

A year later, issues of identity and authority seemed more pressing than taxes in the remainder of unincorporated Lakewood. In March 1953, the Long Beach City Council enabled the Greater Lakewood Annexation Committee to add three more Lakewood neighborhoods to the four already in progress toward annexation elections. (The city council had rejected an earlier plan, proposed by the Lakewood Chamber of Commerce, to hold a single, Lakewood-wide vote.)

By April, there were nine annexation areas – from South Street in the north to Willow Street in the south – heading toward an annexation election. According to John Todd, the Lakewood Taxpayers’ Association was being tom apart by a nearly equal division of those in favor of and opposed to annexation.

The battle expanded in May with the creation of the Lakewood Civic Council (LCC). Organized expressly for the anti-annexation fight, LCC members included attorney John Todd, attorney Angelo Iacoboni, realtor Gene Nebeker, Don Rochlen, Guy Halferty, Lee Hollopeter, Francis Veeder, Jacqueline Rynerson, Los Angeles Times reporter William Burns, Ed Walker, and Jim Knox, among several others. (Rynerson began nearly 40 years of public service as the secretary civic council.)

The Lakewood Park Corporation brought in three executives whose involvement would be crucial. Lee Hollopeter had been a Montana Land Company employee who was retained by the Lakewood Park Corporation to manage the Lakewood Water and Power Company. Hollopeter would serve as a liaison between Lakewood's three developers and Todd's growing circle of incorporation advocates. (Video: John Todd and incorporation)

Guy Halferty was retained as a community organizer by the Lakewood Park Corporation and the Southern California Gas Company. He would become the office manager of the incorporation committee in 1953 (and eventually become Lakewood's spokesman).

Don Rochlen was the public relations representative of the Lakewood Park Corporation. He would have the most visible role in the anti-annexation and pro-incorporation movements.

Don Rochlen (center), working for the Lakewood Park Corporation, helped organize Lakewood residents.

Don Rochlen (center), working for the Lakewood Park Corporation, helped organize Lakewood residents.

The anti-annexation (and later, the pro-incorporation) movement benefited from at least $70,000 in corporate funding, mostly from Lakewood’s developers, although both the Southern California Gas Company and Prudential Insurance had an interest in preventing annexation by Long Beach and may also have aided in financing the two campaigns.

Pro-annexation support largely came from the Long Beach Press-Telegram in the form of editorials and in the opinion columns of the paper’s regular columnists. The Press-Telegram then – and for decades after – represented Long Beach’s political power structure and was closely allied with Long Beach business interests and the downtown department stores that faced competition from Lakewood Center.

Conservative in outlook and comfortable with segregation, Long Beach's municipal politics were closed to the Jewish developers of Lakewood and unwelcoming to the socially and culturally diverse community of young men and women who were moving into Lakewood homes.

With annexation elections just weeks away, John Todd had an idea to outfox Long Beach’s piece-by-piece annexation scheme. Under state law, Todd said, petitions to hold an annexation election in a tract had to be circulated among the property owners before an election could be scheduled. To be valid, the annexation petition needed signatures from 25% of the area’s voters. But if 50% of the property owners in an annexation area protested the election to the county Board of Supervisors, the election could not be called, and another attempt at annexation would have to wait an entire year.

The problem was time. Opponents of annexation would need time to compile the names of property owners in the annexation area, prepare a protest petition, set up a neighborhood organization, and circulate protest petitions so that they could be signed. Despite these limitations, Todd concluded that state law actually gave anti-annexation protesters a huge advantage.

Todd asserted that “anytime after the proponents had published the Notice of Intention to circulate annexation petitions, the protest petitions could be circulated.” Under state law, the proponents of annexation had to wait 21 days after the publication of the Notice of Intention before they could circulate their annexation election petitions. That gave the anti-annexation organization nearly a month to circulate their protest petitions before pro-annexation petitions were circulated.

Long Beach city officials rejected Todd’s novel legal strategy. The Long Beach City Council began holding annexation elections despite protest petitions filed by the LCC. In response, Todd struck back with a lawsuit.

“On August 7, 1953, Judge Frank Swain, presiding in Department 34 of the Superior Court, rendered a decision that had a more profound effect upon my legal practice than any other decision,” Todd wrote in his memoir. “Judge Swain held that our protests were valid and that the city of Long Beach had invalidly refused to consider our protest, failed to give us a fair hearing, and that the annexation (election) … was void. Our procedure therefore was valid. Everything I had gambled on had succeeded.”

Todd and the LLC used the same procedure in the following weeks. “Prior to the annexation election, we would go to court and obtain an order in Judge Swain’s department invalidating the Long Beach election. As a matter of fact, it got to the point where we were invalidating elections that probably really had been validly held by the city of Long Beach. We just couldn’t seem to lose.”